By 2025, more than 1 in 5 prescription drugs in the U.S. and Europe are at risk of running out - not because of a single factory shutdown, but because of a web of interconnected failures. It’s not just about one company running out of active ingredients. It’s about water shortages in India slowing down API production, tariffs making raw materials 40% more expensive, and aging manufacturing plants in China that haven’t been upgraded since 2015. The drug shortages we’re seeing today are symptoms. The real problem is what’s coming next.

Why Drug Shortages Are Getting Worse

Drug shortages aren’t random. They follow patterns. The World Health Organization reported 1,700 global drug shortages in 2024 - up 38% from 2020. That’s not a spike. It’s a trend. And it’s accelerating. The main drivers? Three things: supply chain fragility, regulatory delays, and economic pressure.

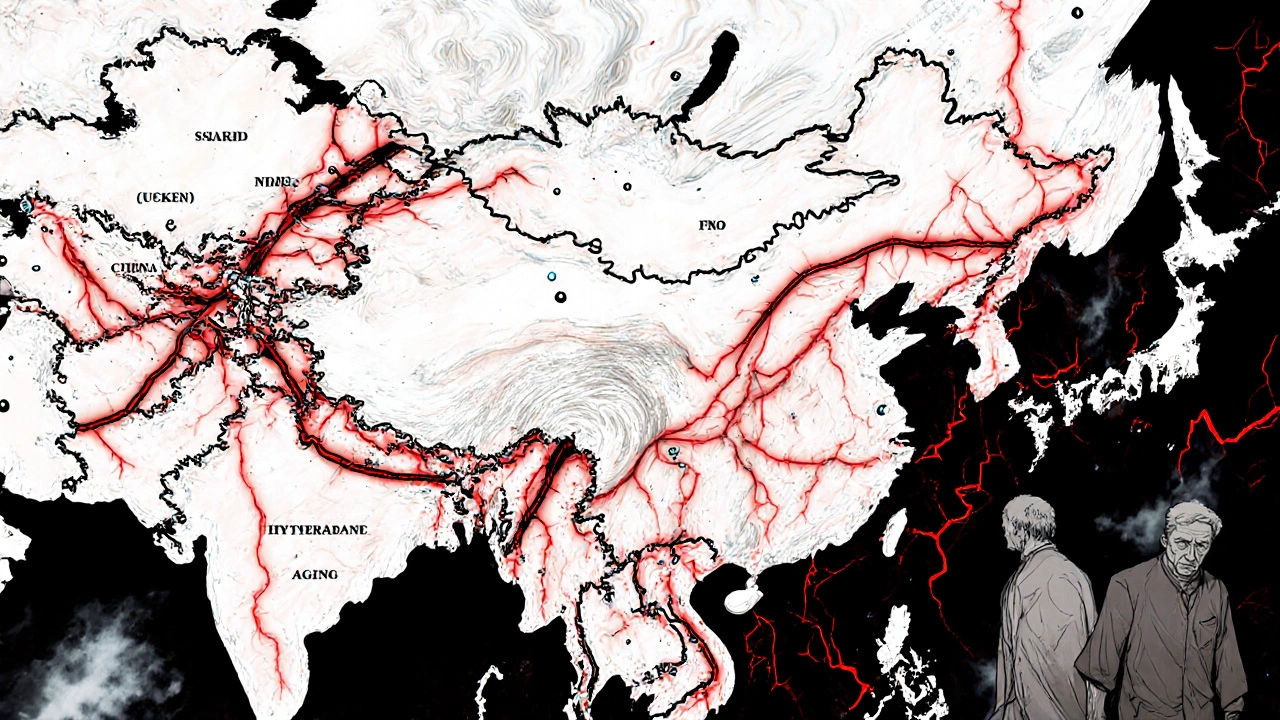

Let’s start with supply chains. Over 80% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in U.S. medications come from just two countries: India and China. Both are under stress. In India, groundwater levels have dropped 60% in the last 20 years in key manufacturing regions like Hyderabad and Ahmedabad. Water is needed to cool reactors, clean equipment, and dilute chemical waste. When water runs low, production halts. In China, energy rationing during winter months has forced 12 major API plants to cut output by 30% since 2023. These aren’t temporary fixes. They’re structural.

Then there’s regulation. The FDA takes an average of 18 months to approve a new supplier for a generic drug. Meanwhile, the existing supplier might be running at 98% capacity. If something breaks - a pipe, a filter, a power outage - there’s no backup. And because generics make up 90% of prescriptions, there’s no profit incentive for companies to build redundancy. Why spend $50 million on a second plant when you can make the same profit from one?

And economics? Generic drug prices have been falling for 15 years. The average price of a 30-day supply of metformin dropped from $12 in 2010 to $1.20 in 2024. Companies are squeezing every penny. That means no extra inventory. No safety stock. One delay - a shipping strike, a customs hold, a lab contamination - and the drug vanishes from shelves.

Which Drugs Are Most at Risk?

It’s not just obscure drugs. The most common, most essential medicines are the ones disappearing.

- Insulin: Over 10 million Americans rely on it. Production is concentrated in three plants worldwide. One of them had a contamination issue in early 2025 - shelves went empty for six weeks.

- Levothyroxine: Used by 25 million people for hypothyroidism. The API comes from a single supplier in China. No alternatives. No backups.

- Vancomycin: A last-resort antibiotic. Production requires sterile conditions. Only five facilities globally meet the standard. Two are over 30 years old.

- Procaine penicillin: Still used in rural clinics and developing nations. Made in one factory in India. That factory had a 14-day shutdown in March 2025 due to a water shortage.

- Methotrexate: Used for cancer and autoimmune diseases. One company controls 85% of global supply. They raised prices 200% in 2024 and cut production volume to boost margins.

These aren’t niche cases. These are drugs that keep people alive. And the systems keeping them in stock are barely holding on.

How Forecasting Works - And Why It’s Failing

Pharmaceutical companies and health agencies use forecasting models that look like this: past sales data + production capacity + regulatory timelines. Simple. Flawed.

They don’t factor in climate stress. They don’t track water tables in Gujarat. They don’t model how U.S. tariffs on Chinese chemicals affect Indian manufacturers who import those chemicals. They don’t account for the fact that 40% of the world’s API production workers are over 50 and retiring without replacements.

Real forecasting now needs to combine:

- Climate data: rainfall, drought, heat waves in manufacturing zones

- Geopolitical risk: trade wars, export bans, sanctions

- Labor trends: retirement rates, immigration policies, training pipelines

- Energy costs: natural gas prices in Europe, coal shortages in India

- Supply chain visibility: real-time tracking of API shipments, not just end-product inventory

Only a handful of organizations do this. The WHO’s Global Observatory on Medicine Shortages is one. The U.S. FDA’s Drug Shortages Program is another. But they’re underfunded and reactive. Most forecasts are still based on last year’s numbers. By the time a shortage is flagged, it’s already happening.

What’s Changing in 2025-2030

The next five years will change everything.

First, energy transition costs. As countries push for greener manufacturing, old chemical plants face expensive retrofits. Many will shut down instead. The International Energy Agency estimates 15% of global API production capacity will be offline by 2027 due to compliance costs.

Second, labor collapse. The average age of a pharmaceutical chemist in China is 52. In India, it’s 49. No new graduates are entering the field. The number of chemistry degrees awarded in China fell 22% between 2018 and 2024. Who’s going to make the drugs when the current workers retire?

Third, regional fragmentation. Countries are starting to build local supply chains. The EU passed the Pharmaceutical Strategy in 2024, requiring 50% of essential drugs to be made within Europe by 2030. The U.S. is funding domestic API production through the CHIPS and Science Act. India is banning exports of 24 critical APIs to protect its own supply. This sounds good - until you realize it means less global efficiency. Fewer plants, higher prices, slower response times.

And fourth, AI-driven demand shifts. New cancer drugs, diabetes treatments, and rare disease therapies are hitting the market. But they’re expensive. Hospitals can’t afford to stock them in bulk. So they order just-in-time. That leaves zero buffer. One delay - and a patient goes without.

What Can Be Done?

There’s no magic fix. But there are proven steps.

1. Build strategic stockpiles. The U.S. Strategic National Stockpile holds vaccines and antidotes. Why not essential drugs? A 6-month reserve of insulin, levothyroxine, and antibiotics could prevent mass disruptions. It costs less than treating the fallout of a shortage.

2. Mandate multi-sourcing. Require manufacturers to have at least two approved API suppliers for every essential drug. The EU already does this for 12 high-risk medicines. It works.

3. Fund domestic capacity with real incentives. Tax breaks aren’t enough. Governments need to pay upfront for new plants. The U.S. government paid $1.2 billion to build a single API facility in North Carolina - and it’s now producing 30% of the country’s metformin.

4. Use real-time data. Track shipments, water levels, energy use, and worker shifts at production sites. A startup in Boston, MedSupplyAI, already does this. They monitor 400+ API plants globally. Their model predicted the 2025 vancomycin shortage six months before it happened. Only the FDA hasn’t adopted it.

5. Reward reliability over price. Stop buying the cheapest generic. Pay more for suppliers with backup plans, modern equipment, and transparent reporting. Hospitals and insurers can lead this change.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or someone you know relies on a medication that’s been on shortage lists - like metformin, levothyroxine, or amoxicillin - don’t wait.

- Ask your pharmacist: Is there an alternative? Is there a different manufacturer?

- Sign up for FDA drug shortage alerts.

- Keep a 30-day supply on hand - if your insurance allows it.

- Join patient advocacy groups. Pressure lawmakers. Drug shortages aren’t inevitable. They’re policy choices.

The next time you hear a drug is unavailable, don’t assume it’s just bad luck. It’s the result of decisions made over decades - and we’re still making them. The question isn’t whether more shortages will happen. It’s whether we’ll act before someone dies because we didn’t.

Why are generic drugs more likely to be in short supply than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs have razor-thin profit margins - often less than 5%. Manufacturers don’t invest in backup suppliers, modern equipment, or inventory buffers because there’s no financial reward. Brand-name drugs, by contrast, have higher prices and longer patent protection, so companies can afford to maintain multiple production lines and safety stock. When a crisis hits, generics are the first to vanish.

Can the U.S. make its own drugs again?

Yes - but it’s expensive and slow. The U.S. has started rebuilding domestic API capacity, with new plants in North Carolina, Ohio, and Puerto Rico. But building a single FDA-approved facility takes 5-7 years and costs $300 million to $1 billion. Even if every plant built today came online in 2028, it would only cover 15-20% of current needs. Domestic production isn’t a full solution - it’s part of one.

How does climate change directly affect drug production?

Many API factories need massive amounts of clean water for cooling and chemical processing. In India, groundwater levels have dropped so low that some plants can’t operate during dry seasons. In China, extreme heat waves force factories to shut down to avoid equipment failure. Droughts and floods disrupt transportation routes. Climate isn’t a future threat - it’s already cutting production.

Are drug shortages getting worse in Australia?

Australia imports over 90% of its medicines. When shortages hit the U.S. or Europe, Australia feels them too - often with a 2-4 week delay. In 2024, Australia saw shortages of insulin, levothyroxine, and antibiotics due to global supply chain issues. Local manufacturing is minimal, so the country is highly vulnerable to international disruptions.

What’s the difference between a drug shortage and a drug recall?

A recall happens when a drug is unsafe - contaminated, mislabeled, or defective. The FDA pulls it off shelves. A shortage means the drug is safe and effective, but there’s not enough of it to meet demand. No one did anything wrong - the system just broke. Shortages are about supply. Recalls are about safety.

What Comes Next

By 2030, we’ll either have a resilient, diversified, and transparent drug supply - or we’ll be living with routine, life-threatening shortages. There’s no middle ground. The systems we have now were built for a world that no longer exists. The cost of doing nothing isn’t just higher prices. It’s missed doses, delayed treatments, preventable deaths.

Forecasting isn’t about predicting the future. It’s about changing it.

Author

Mike Clayton

As a pharmaceutical expert, I am passionate about researching and developing new medications to improve people's lives. With my extensive knowledge in the field, I enjoy writing articles and sharing insights on various diseases and their treatments. My goal is to educate the public on the importance of understanding the medications they take and how they can contribute to their overall well-being. I am constantly striving to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in pharmaceuticals and share that knowledge with others. Through my writing, I hope to bridge the gap between science and the general public, making complex topics more accessible and easy to understand.