When someone is diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the question isn’t just what happens next-it’s how much time they have. ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, doesn’t just weaken muscles. It slowly kills the nerve cells that control movement. Once those motor neurons die, they don’t come back. There’s no cure. But there is one drug that has, for nearly 30 years, given people a few extra months-riluzole.

What ALS Does to the Body

ALS attacks both upper and lower motor neurons. These are the nerves that connect your brain to your muscles. When they break down, your muscles stop getting the signal to move. At first, it might be a stumble, a dropped spoon, or trouble speaking clearly. Then comes weakness in the arms, legs, and eventually the muscles that let you breathe. Most people live 3 to 5 years after symptoms start. A small number survive longer, but the disease is always fatal.

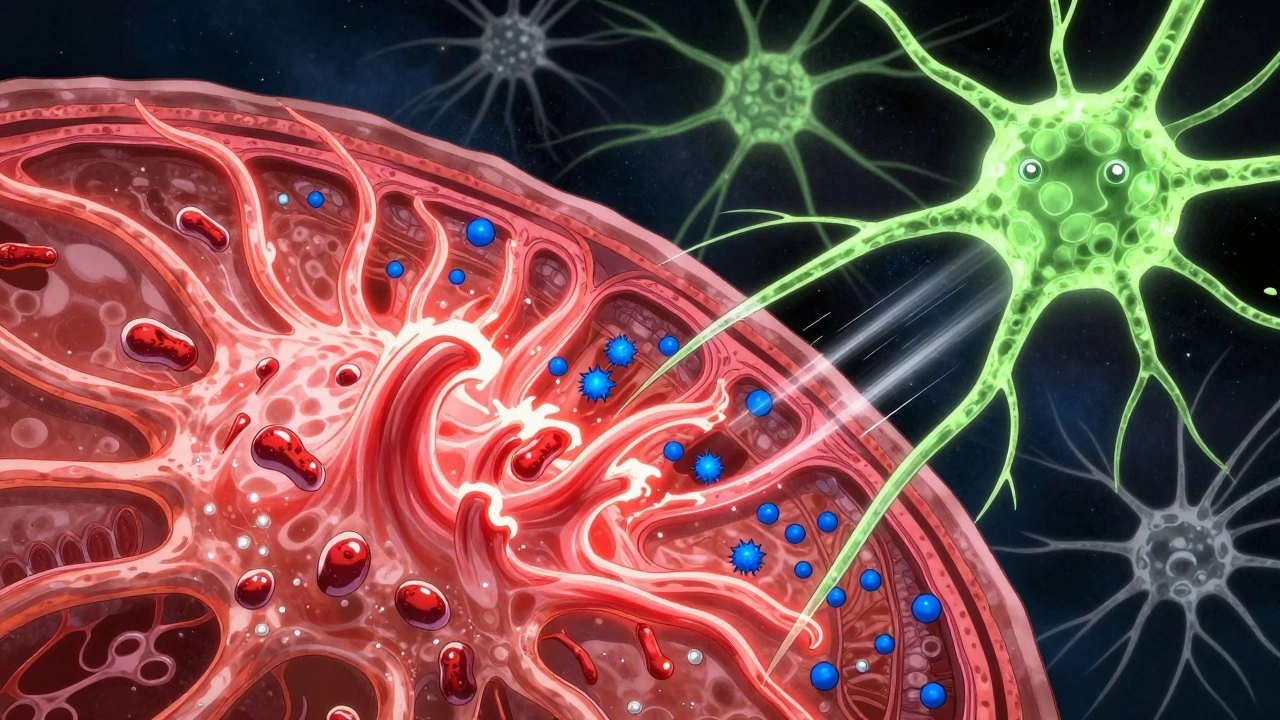

What makes ALS so deadly isn’t just the muscle loss-it’s the hidden damage happening inside the nervous system. One key player is glutamate, a chemical messenger in the brain. Too much of it, and nerve cells get overstimulated, like a circuit burning out. This is called excitotoxicity. In ALS, the body can’t clear glutamate fast enough, and neurons start dying from the inside out.

Riluzole: The First Drug That Actually Helped

Before 1995, there was nothing. No drug, no treatment, no hope of slowing the disease. Then came riluzole. Approved by the FDA on May 24, 1995, it was the first-and for over two decades, the only-medication shown to extend life in ALS patients.

Riluzole doesn’t reverse damage. It doesn’t restore movement. But in clinical trials, it reduced the risk of death or needing a breathing tube by 35% to 39% after 18 months. That sounds small, but in a disease with no other options, even a few extra months matter. The average survival increase? About 2 to 3 months. For some, it’s more. For others, less. But for many families, those months mean seeing a child graduate, attending a wedding, or simply having one more breakfast together.

It’s not magic. It’s science. Riluzole works in three ways: it blocks excess glutamate release, shuts down sodium channels that overfire in damaged nerves, and interferes with the signals that trigger cell death. It’s a small molecule-just 235 grams per mole-but its impact has been huge. For 22 years, it stood alone as the only disease-modifying treatment for ALS.

How It’s Taken-and What It Costs

Riluzole comes in three forms: tablets (Rilutek), oral suspension (Tiglutik), and an oral thin film (Exservan). The standard dose is 100 mg per day, split into two 50 mg doses. Most people start with one pill a day for a week, then move to twice daily. It’s absorbed about 60% into the bloodstream, and it peaks in the blood within an hour and a half. But it doesn’t last long-half of it is gone in 7 to 15 hours. That’s why you need to take it twice a day, no matter how tired you are.

It’s not cheap. Worldwide, riluzole makes up about 35% of the ALS drug market, generating $445 million in sales annually. In the U.S., a month’s supply can cost over $1,000 without insurance. Many patients rely on patient assistance programs. In low-income countries, fewer than 1 in 5 people can afford it at all.

Side Effects: The Trade-Off

Riluzole isn’t easy to tolerate. About 25% of users get nausea. 15% have diarrhea. 20% feel unusually tired. And 12% see their liver enzymes rise-sometimes dangerously. That’s why doctors require blood tests before you start and every month for the first three months. If your liver numbers climb too high, you stop.

One Reddit user wrote: “Nausea was brutal the first 3 months. Took it with food. Now it’s fine. My neurologist says I’m progressing slower than most. I don’t know if it’s the riluzole-but I’m taking any chance I get.”

Another said: “My liver enzymes tripled after 9 months. I had to stop. It’s frustrating when the only drug that might help damages your liver.”

That’s the reality. About 10% to 15% of people quit because of side effects. But 62% of patients surveyed keep taking it anyway. Why? Because even a small chance of more time is worth the nausea, the fatigue, the monthly blood draws.

How It Compares to Other ALS Drugs

In 2017, edaravone (Radicava) became the second FDA-approved ALS drug. It works differently-it’s an antioxidant that fights oxidative stress. In trials, it slowed functional decline by 33% over 6 months. But unlike riluzole, it hasn’t been shown to extend life. It’s also given as an IV infusion, 14 days a month, which is hard for people already struggling to move.

In 2023, tofersen (Qalsody) got approved for a rare genetic form of ALS caused by SOD1 mutations. It’s a gene-targeted therapy, but it only helps about 2% of patients. And it’s given by spinal injection.

Riluzole still works for everyone. It’s oral. It’s been studied in tens of thousands of patients. It’s the baseline. Even when new drugs come out, doctors still start with riluzole. It’s not the best option for everyone-but it’s the only one that’s been proven to help across the board.

Who Should Take It-and Who Shouldn’t

If you’re newly diagnosed with ALS, your doctor will almost certainly recommend riluzole. The American Academy of Neurology gives it a Level A recommendation-the strongest possible-based on multiple high-quality studies. It’s not optional. It’s standard.

But there are exceptions. If you have moderate to severe liver disease, you shouldn’t take it. The drug builds up in your system and can cause serious harm. If you’re on theophylline (for asthma), riluzole can make its levels spike dangerously. Caffeine can reduce how well riluzole works, so heavy coffee or energy drink users may need to cut back.

Renal failure? No problem. Riluzole doesn’t rely on the kidneys. But liver health? That’s critical.

The Real Impact: More Than Just Numbers

Statistically, 2 to 3 months doesn’t sound like much. But in ALS, time is everything. It’s not just about living longer. It’s about living with dignity. It’s about being able to say goodbye properly. It’s about watching your grandchild take their first steps instead of being too weak to hold them.

A 2022 survey of nearly 3,000 ALS patients found that 78% started riluzole after diagnosis. At one year, 63% were still on it. At two years, nearly half were still taking it. That’s not because it’s easy. It’s because, for many, it’s the only thing standing between them and faster decline.

Dr. Hiroshi Mitsumoto, a leading ALS expert at Columbia University, put it plainly: “In a uniformly fatal disease with no cure, this represents a meaningful therapeutic advance.”

The Future: Riluzole in Combination Therapy

Riluzole isn’t the end of the story. Researchers are now testing it with other drugs. One promising combo is riluzole plus sodium phenylbutyrate, which may help protect nerve cells in a different way. Early results from a Phase 2 trial are expected in mid-2024.

Even with new gene therapies and antioxidants on the horizon, riluzole is likely to remain a cornerstone. Why? Because it’s simple, safe for most, and proven. It doesn’t fix ALS. But it buys time. And in a disease where every day counts, that’s everything.

Author

Mike Clayton

As a pharmaceutical expert, I am passionate about researching and developing new medications to improve people's lives. With my extensive knowledge in the field, I enjoy writing articles and sharing insights on various diseases and their treatments. My goal is to educate the public on the importance of understanding the medications they take and how they can contribute to their overall well-being. I am constantly striving to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in pharmaceuticals and share that knowledge with others. Through my writing, I hope to bridge the gap between science and the general public, making complex topics more accessible and easy to understand.