Getting an insulin pump isn’t like swapping out a phone. It’s a life-changing tool, but only if you know how to use it right. Too many people think the pump does the work for them-until they wake up with dangerously low blood sugar or end up in the hospital with diabetic ketoacidosis. The truth? Insulin pump therapy demands your attention, every single day.

What’s Inside an Insulin Pump?

An insulin pump isn’t magic. It’s a small device that delivers rapid-acting insulin through a tiny tube inserted under your skin. No long-acting insulin needed. Just Humalog, Novolog, or similar analogs. The pump gives you two kinds of insulin: a steady drip (basal) and a quick burst (bolus) for meals or corrections.Basal rates are programmed to change throughout the day. Your body doesn’t need the same amount of insulin at 3 a.m. as it does at noon. Most pumps let you set different basal profiles-for weekdays, weekends, sickness, or exercise. If your basal is too high, you’ll crash. Too low, and your numbers climb. Testing it properly isn’t optional. You need to fast for at least 24 hours, avoid exercise, and check your blood sugar every 2 hours. If your glucose stays steady, your basal is right. If it drops or rises, you adjust.

Setting Your Bolus: More Than Just Carbs

Boluses aren’t just ‘carbs divided by ratio.’ There’s more to it. Your insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR) tells you how many grams of carbs one unit of insulin covers. A typical starting point is 1:10, but that’s just a guess. Your actual ratio might be 1:8 or 1:15. You figure it out by testing after meals, tracking your numbers, and adjusting slowly.Then there’s your insulin sensitivity factor (ISF)-how much one unit of insulin lowers your blood sugar. For most adults, it’s around 1:3 to 1:5 mmol/L. So if your sugar is 12 mmol/L and your target is 6 mmol/L, you’re 6 points high. Divide that by your ISF (say, 4), and you need 1.5 units to correct it.

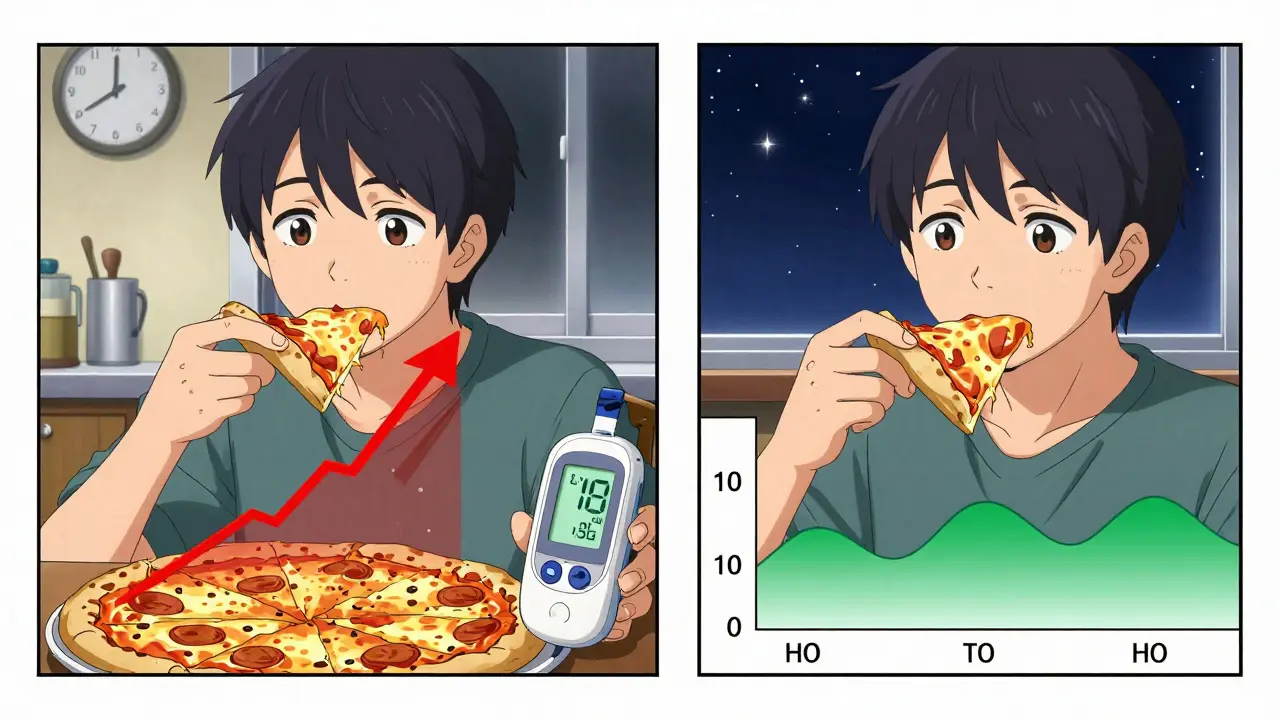

But here’s the catch: not all meals are the same. A pizza or a curry doesn’t spike your sugar right away. That’s where extended or dual-wave boluses come in. You can split the dose-give half now, half over two hours. Most people don’t use this feature. They should. It cuts down on late-night highs.

Infusion Sets and Site Care

Your cannula goes in the belly, thigh, or upper arm. Change it every 2 to 3 days. No exceptions. Leaving it in longer doesn’t save money-it increases infection risk. One in three new pump users gets redness, swelling, or bumps at the site within the first three months. That’s not normal. That’s poor site rotation.Rotate your sites like clockwork. Don’t reuse the same spot. If you’ve had a bump or hard lump there before, avoid it. Lipohypertrophy-fatty lumps from repeated injections-can make insulin absorb unpredictably. That’s why your numbers go wild even when you think you did everything right.

Safety First: What Can Go Wrong

The biggest fear? Pump failure. A disconnected tube, a kinked line, an empty reservoir. You might not notice. And in 2 to 4 hours, your body starts burning fat for fuel. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) can sneak up fast. That’s why you check your blood sugar every few hours, especially after a site change or if you feel off.If your sugar is over 13 mmol/L and you’re feeling sick, test for ketones. No ketones? Maybe you just need a correction. Ketones present? Change your infusion set immediately, give a bolus, and drink water. If you’re dizzy, vomiting, or confused-go to the hospital. Don’t wait.

Another risk? Sleep. If you’re unconscious and your pump keeps delivering insulin, you could die. That’s why all modern pumps have automatic low-glucose suspend. If your glucose drops below a set point, the pump stops insulin for 30 to 120 minutes. It’s not perfect, but it’s lifesaving. Still, never rely on it alone. Always keep glucose tabs in your pocket, your phone charged, and someone who knows what to do if you can’t speak.

Special Situations: Surgery, Pregnancy, and Travel

Need surgery? If it’s minor and you’ll eat within a few hours, your pump can stay on-if your glucose is between 4 and 12 mmol/L, your reservoir is full, and the site is accessible. For major surgery? You’ll switch to IV insulin. Your care team will handle it. Don’t try to wing it.After giving birth, your insulin needs drop fast. Many women cut their total daily dose by 20% or more. If you’re breastfeeding, you might need even less. Your pump settings aren’t permanent. They change with your body.

Traveling? Always carry twice the supplies you think you’ll need. Extra infusion sets, batteries, insulin vials, syringes. A backup plan isn’t optional. Airlines don’t care about your pump. But they’ll let you bring it onboard. Keep it with you. Never check it.

Technology and Trends

The latest pumps are smarter. The Tandem Mobi is tiny-small enough for a child’s pocket. The Omnipod 5 works with multiple CGMs, not just one brand. The Medtronic 670G adjusts basal insulin automatically. But here’s the thing: none of them replace you.These systems still need you to tell them when you eat. They still need you to check your glucose. They still need you to change your tubing. The tech helps. It doesn’t do the work.

By 2028, nearly 40% of people with type 1 diabetes will use a pump. But cost is still a barrier. In the U.S., it runs $6,500 to $8,200 a year. That’s more than daily injections. Insurance helps, but not always enough. If you’re struggling, talk to your diabetes educator. There are assistance programs.

Getting Started Right

Don’t start on a Friday. Start on a Monday. That way, your diabetes team is in the office if something goes wrong. Training takes at least 15 hours. You need to learn how to insert a site, program a basal rate, calculate a bolus, troubleshoot a kink, and respond to low glucose.Most people get the basics in 2 to 4 weeks. Mastery? That takes 3 to 6 months. You’ll make mistakes. You’ll overbolus. You’ll forget to change your site. That’s normal. What’s not normal is giving up.

Use your pump’s data. Download it every week. Look at your trends. See where your highs and lows happen. Adjust. Repeat. This isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it device. It’s a partner. And like any good partner, it needs your input to work well.

What the Experts Say

Dr. Anne Peters puts it bluntly: “CSII is not an artificial pancreas.” It’s a tool. And tools are only as good as the hands that use them. Dr. John Walsh says the most common error? Bad basal rate testing. You can’t guess it. You have to test it.People who succeed with pumps do three things: they count carbs accurately, they check glucose often, and they never ignore alarms. The ones who struggle? They skip checks. They don’t test ketones. They leave their tubing in too long.

If you’re considering a pump, ask yourself: Can I check my blood sugar at least four times a day? Do I understand insulin action times? Am I willing to learn the tech and stick with it? If yes-you’re ready. If not, talk to your team. There’s no rush.

Insulin pumps don’t cure diabetes. But done right, they give you back your life. More freedom. Fewer crashes. Better sleep. Better A1c. But only if you show up every day.

How often should I change my insulin pump infusion set?

Change your infusion set every 2 to 3 days. Leaving it in longer increases the risk of infection, poor insulin absorption, and lipohypertrophy. Even if the site looks fine, insulin delivery becomes less reliable after 72 hours.

What’s the difference between basal rate and bolus?

Basal rate is the small, continuous amount of insulin your pump delivers 24/7 to manage blood sugar between meals and overnight. Bolus is the extra insulin you give yourself for meals or to correct high blood sugar. Basal keeps you stable; bolus handles spikes.

Can I use an insulin pump if I have type 2 diabetes?

Yes-but only if you require intensive insulin management and have unstable blood sugar despite other treatments. The American Diabetes Association recommends pumps for type 2 patients who need multiple daily injections and struggle with hypoglycemia or erratic glucose patterns. It’s not for everyone with type 2, but it’s an option for those who need precision.

What should I do if my pump stops working?

If your pump stops, switch to insulin injections immediately. Use your backup insulin and syringes. Give your usual basal dose as long-acting insulin (if prescribed), or split your total daily dose into two or three injections of rapid-acting insulin every 3 to 4 hours. Never go without insulin. Contact your diabetes team and get a replacement pump as soon as possible.

How do I know if my basal rate is correct?

Test your basal by fasting for 24 hours-no food, no exercise, no boluses. Check your blood sugar every 2 hours. If it stays within 1 mmol/L of your target (e.g., 5.5 to 6.5 mmol/L), your basal is right. If it drops, your basal is too high. If it rises, it’s too low. Adjust in small increments (0.05 to 0.1 units per hour) and retest after 24 hours.

Do insulin pumps reduce hypoglycemia?

Yes-when used correctly. Studies show users on pumps with CGM integration have fewer severe lows compared to those on multiple daily injections. Automated systems like the Medtronic 670G suspend insulin before glucose drops too low. But pumps don’t eliminate hypoglycemia. You still need to monitor, adjust, and respond. The pump helps, but you’re still in charge.

What’s the biggest mistake new pump users make?

Assuming the pump will fix everything. The biggest mistake is skipping carb counting, not testing blood sugar often enough, and ignoring site rotation. Pump users who don’t track their data or adjust settings based on results often end up with worse control than before. The pump doesn’t think for you-it just delivers what you tell it to.

Author

Mike Clayton

As a pharmaceutical expert, I am passionate about researching and developing new medications to improve people's lives. With my extensive knowledge in the field, I enjoy writing articles and sharing insights on various diseases and their treatments. My goal is to educate the public on the importance of understanding the medications they take and how they can contribute to their overall well-being. I am constantly striving to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in pharmaceuticals and share that knowledge with others. Through my writing, I hope to bridge the gap between science and the general public, making complex topics more accessible and easy to understand.