When you fill a prescription for blood pressure medication or antibiotics, there’s a good chance you’re not getting the brand-name drug. You’re probably holding a generic drug-a chemically identical version that costs a fraction of the original. But while this might feel like a standard part of healthcare in the U.S., the way countries manage generics varies wildly across the globe. Some nations have turned generics into a powerful tool to slash drug spending. Others struggle with shortages, quality concerns, or bureaucratic delays that block access. Understanding how different countries handle generics isn’t just about policy-it’s about who can afford to live with chronic illness, who gets left behind, and what happens when profit margins disappear.

How Generics Work: The Basic Idea

Generic drugs are not knock-offs. They must meet strict standards to prove they deliver the same active ingredient, in the same strength, and with the same effect as the original brand. The key metric is bioequivalence: the generic must absorb into the bloodstream at nearly the same rate and level as the brand-name version. Regulatory agencies like the U.S. FDA and the European EMA require this proof before approval. But here’s the catch: proving bioequivalence doesn’t mean the pill is identical in every way. Fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes can differ. For most people, this doesn’t matter. For others-especially those taking anticoagulants, epilepsy drugs, or thyroid medications-small differences can trigger serious side effects. That’s why some countries restrict generic substitution for these high-risk drugs.

The U.S. Model: High Use, High Prices

The United States fills 90.1% of prescriptions with generics-the highest rate among developed nations. That’s not because Americans are more willing to switch. It’s because the system is built to make it easy. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a fast-track approval process for generics, and the FDA has approved over 11,300 generic products as of late 2024. Companies can file abbreviated applications instead of running full clinical trials. And with Medicare and Medicaid negotiating bulk prices, generic drugs are often priced below $5 per month.

But here’s the paradox: even though generics dominate prescriptions, the U.S. still has the highest overall drug prices in the world. Why? Because brand-name drugs, especially new biologics and specialty medications, carry enormous price tags. Generics keep millions affordable, but they don’t pull down the average because they’re not the expensive ones. The result? Medicare saved $142 billion in 2024 from generic use alone-$2,643 per beneficiary. That’s huge. But if you need a $10,000-a-month cancer drug, generics won’t help. The system works brilliantly for common conditions, but fails to address the cost of innovation.

Europe’s Fragmented System: Same Drug, Different Prices

Across the European Union, generics make up 65% of all prescriptions dispensed-but only 22% of total drug spending. That’s because European countries have strong price controls. Germany, for example, uses mandatory generic substitution: pharmacists must switch you to the cheapest available version unless your doctor blocks it. In Italy, that rate is just 67%-because doctors and patients still trust brands more.

The real problem? Price variation. Identical generics can cost 300% more in one country than its neighbor. A 10mg tablet of amlodipine might cost €0.12 in Germany but €0.48 in Spain. Why? Because each country sets its own reimbursement rates. The European Medicines Agency approves the drug, but then 27 different governments decide how much they’ll pay. This creates chaos. Manufacturers can’t plan production. Pharmacies can’t stock efficiently. And patients traveling between countries get confused-or worse, can’t refill their meds.

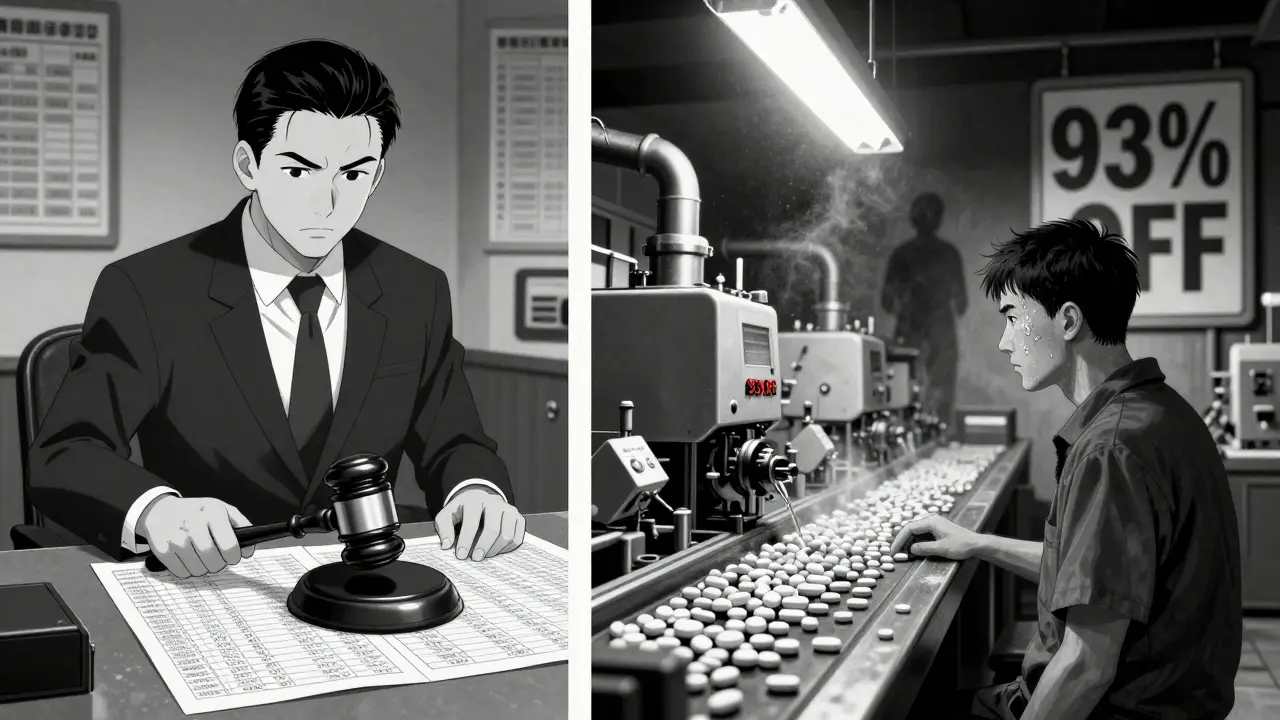

China’s Volume-Based Procurement: The Hammer Approach

In 2018, China launched a radical experiment: Volume-Based Procurement (VBP). Instead of letting hospitals negotiate prices individually, the government held centralized auctions. The lowest bidder wins the right to supply 80% of the country’s hospital demand for that drug. The result? Average price drops of 54.7%. In some cases-like the heart drug eplerenone-prices plunged 93%.

It worked. Billions in savings. But it came at a cost. Many manufacturers couldn’t produce the drug profitably at those prices. Some cut corners. Others just stopped making it. In 2024, 12 Chinese provinces faced a six-week shortage of amlodipine because the winning bidder couldn’t meet demand. A survey by the China Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 23% of manufacturers were operating at a loss on VBP-contracted drugs. The government is now expanding VBP to 150 more drugs in January 2026, with winning bids expected to be 65% below current prices. The question isn’t whether this will save money-it will. The question is whether the supply chain will hold.

India: The Pharmacy of the World

India produces 20% of the world’s generic medicines by volume. It’s the largest supplier of affordable drugs to Africa, Latin America, and the U.S. This isn’t accidental. India’s patent laws allow compulsory licensing-meaning if a drug is too expensive, the government can authorize a local company to copy it. This is how India supplied 80% of the HIV antiretrovirals used in developing countries during the 2000s.

But this model has a dark side. The FDA issued 2,183 import alerts for Indian manufacturers in 2024-up from 1,247 in 2020. Many of these were for data integrity issues: fake lab results, missing records, or altered test data. Indian doctors report that 58% of generics-especially for epilepsy and blood thinners-show inconsistent bioavailability. Patients get seizures or clots because the dose isn’t reliable. The government is trying to fix this. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) cut approval times from 36 months to 14 months. But enforcement still lags. India’s strength is volume. Its weakness is consistency.

South Korea: The Precision Model

South Korea didn’t just lower prices. It engineered a system to control quality and competition at the same time. In 2020, they launched the ‘1+3 Bioequivalence Policy’: only one brand and three generics can be approved for each drug. Then, in 2021, they added the Differential Generic Pricing System. Generics that meet both quality and price standards get priced at 53.55% of the brand. Those meeting only one criterion get 45.52%. The rest? 38.69%.

This system reduced redundant generic entries by 41% between 2020 and 2024. But it also cut new generic launches by 29%. Companies stopped investing because the reward was too small. The result? Fewer competitors. Less pressure to lower prices. Patients still get cheap drugs-but fewer options. It’s a trade-off: control over chaos. And it’s working… for now.

Japan’s Biennial Cuts: Stagnation by Design

Japan doesn’t have a generic boom. It has a price freeze. Every two years, the government forces cuts to both brand and generic drug prices. The goal is to keep drug spending flat. The result? Market stagnation. In 2024, Japan had 76.8% generic use by volume-high, but not growing. Why? Because manufacturers know that if they launch a new generic, it’ll be slashed in price two years later. So they wait. They delay. They focus on markets with better margins. Japan’s generic industry is efficient, but it’s not expanding. It’s surviving.

The Hidden Cost: Quality, Supply, and Innovation

Every country is chasing lower prices. But few are asking: at what cost? When manufacturers operate on 5% margins, they cut testing. They outsource production. They skip audits. The FDA’s warning letters to foreign generic makers jumped 75% from 2020 to 2024. India, China, and even some European suppliers are under scrutiny.

And what about innovation? If every generic is priced to the bone, who will fund the next generation of biosimilars? Who will develop generics for rare diseases? The International Generic and Biosimilars Association warns that excessive price controls could reduce new generic launches by 22-37% in the next decade. That’s not just about cost-it’s about future access.

What Works? What Doesn’t?

There’s no single model that works everywhere. But some principles keep reappearing:

- Transparency works: When patients and doctors know why a generic is cheaper-and trust the data-they accept it. Germany’s education campaigns boosted generic use by 30%.

- Standardization helps: If one country accepts a bioequivalence study from another, approvals get faster. The WHO is pushing for global standards.

- Margins matter: Manufacturers need at least 15-20% gross margin to invest in quality. Anything lower risks shortages and safety issues.

- Price alone isn’t enough: South Korea and China show that controlling price without controlling quality leads to supply failures.

The most successful systems don’t just cut prices-they build trust. They make sure the generic is safe. They make sure it’s available. And they make sure the company making it can stay in business.

The Future: More Patents, More Pressure

Between 2025 and 2030, branded drugs worth $217-$236 billion in annual sales will lose patent protection. That’s the biggest wave of generic opportunity in history. If policies stay the same, it could add $180-$200 billion to the global generic market.

But it won’t be easy. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act will force Medicare to negotiate prices on 10-20 high-cost drugs each year starting in 2028. That could slash brand revenues by 25-35%-and push more patients toward generics. The EU’s new Pharmaceutical Package, expected in late 2025, may harmonize some pricing rules. China’s VBP expansion will tighten the screws further.

The real challenge? Balancing affordability with sustainability. If we drive prices so low that manufacturers quit, we don’t win. We just create new shortages. The goal shouldn’t be the cheapest pill. It should be the most reliable one.

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes, for the vast majority of medications, generic drugs are just as effective. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require generics to prove they deliver the same active ingredient, in the same amount, and with the same effect as the brand. Bioequivalence studies show that absorption rates must fall within 80-125% of the original. For common conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, or depression, generics work just as well. The exception is drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or certain epilepsy meds-where even small differences can cause problems. In these cases, doctors may recommend sticking with the brand or using only generics that have been specifically tested.

Why are generic drugs cheaper if they’re the same?

Generics are cheaper because they don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials. The original brand-name drug company spent years and hundreds of millions developing the drug, running trials, and marketing it. Once the patent expires, generic manufacturers can use that existing data. Their costs are mostly in manufacturing and regulatory paperwork-not research. Plus, competition drives prices down. When five companies make the same generic, they compete on price, not advertising. That’s why a 30-day supply of a generic statin might cost $4, while the brand costs $150.

Can I trust generics made in India or China?

Many generics from India and China are safe and meet international standards. The FDA inspects over 3,000 foreign manufacturing facilities each year, and most comply. But inspections have increased sharply-2,183 import alerts were issued in 2024, up from 1,247 in 2020. Some facilities have been caught falsifying data or cutting corners. The problem isn’t the country-it’s oversight. If a generic is approved by the FDA, EMA, or WHO, it’s been vetted. But if you’re buying from an unregulated online pharmacy, you can’t be sure. Always get generics through licensed pharmacies or public health systems.

Why do some countries have shortages of generic drugs?

Shortages happen when the price is too low for manufacturers to profit. In China, VBP auctions have led to 6-8 week shortages of drugs like amlodipine because the winning bidder couldn’t produce enough at the set price. In the U.S., some generics are discontinued because the market is too small or the profit too thin. When only one company makes a drug and it stops production, there’s no backup. The solution isn’t raising prices blindly-it’s building supply chain resilience: encouraging multiple manufacturers, maintaining buffer stock, and avoiding price cuts that go below manufacturing cost.

Will global generic policies change in the next five years?

Yes. The biggest shifts are coming from China’s expanded VBP program, the EU’s push to harmonize pricing, and the U.S. Medicare drug price negotiation rules. These policies will force manufacturers to choose: compete on price and risk thin margins, or innovate in manufacturing and quality. We’ll likely see fewer generic companies-down from 3,500 to around 2,200 by 2030-and more consolidation. Countries that balance affordability with sustainable margins will keep stable supplies. Those that cut too deep will face recurring shortages. The future belongs to systems that value reliability as much as cost.

Author

Mike Clayton

As a pharmaceutical expert, I am passionate about researching and developing new medications to improve people's lives. With my extensive knowledge in the field, I enjoy writing articles and sharing insights on various diseases and their treatments. My goal is to educate the public on the importance of understanding the medications they take and how they can contribute to their overall well-being. I am constantly striving to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in pharmaceuticals and share that knowledge with others. Through my writing, I hope to bridge the gap between science and the general public, making complex topics more accessible and easy to understand.