Most people assume that if a doctor prescribes a medication, it’s safe - especially when it’s life-saving. But some of the most powerful drugs out there carry a hidden risk: permanent damage to your hearing. This isn’t rare. Every year, millions of people take medications that can quietly destroy the delicate hair cells in their inner ears. And by the time they notice the ringing in their ears or struggle to hear high-pitched voices, it’s often too late. The damage is done.

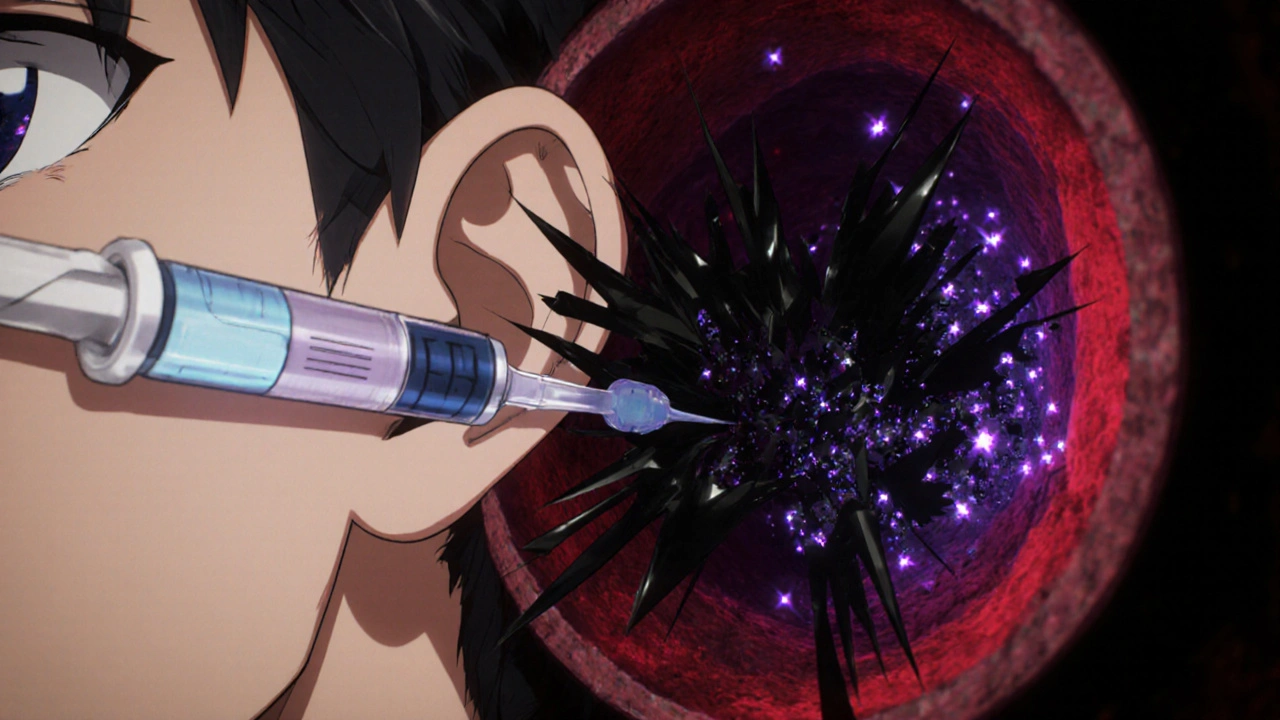

What Exactly Is Ototoxicity?

Ototoxicity means a drug is toxic to your inner ear. It doesn’t just cause temporary muffled hearing - it kills the sensory hair cells that turn sound into electrical signals your brain understands. These cells don’t grow back. Once they’re gone, the hearing loss is permanent.

This isn’t new. Back in the 1940s, doctors first noticed patients on streptomycin - a new antibiotic for tuberculosis - were losing their hearing. Since then, we’ve identified over 600 medications with this risk. The real problem? Many of these drugs are essential. You can’t always swap them out. That’s why knowing the signs and getting proper monitoring isn’t optional - it’s critical.

Which Medications Are the Worst Offenders?

Not all ototoxic drugs are the same. Some are more dangerous than others, and the risk depends on how much you take and how long you’re on them.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics - like gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin - are among the most damaging. Used for serious infections like sepsis or drug-resistant tuberculosis, they can cause hearing loss in 20% to 63% of patients on extended treatment. The higher the dose and the longer the course, the worse it gets. Many patients don’t realize they’re at risk because these drugs are often given in hospitals under close watch - but the hearing damage can sneak up later.

Cisplatin, a chemotherapy drug used for cancers like ovarian, lung, and testicular, is another major culprit. Between 30% and 60% of adults and up to 70% of children treated with cisplatin develop hearing loss. What makes it especially dangerous is that it doesn’t just hurt you while you’re getting the treatment - it lingers in your inner ear for months. Damage can keep getting worse even after your last dose.

Compared to cisplatin, other chemo drugs like carboplatin and oxaliplatin are much safer. But doctors don’t always switch to them, even when possible, because cisplatin works better against certain tumors. That’s why monitoring becomes even more important - you can’t always avoid the drug, but you can catch the damage early.

Even antidepressants like amitriptyline, sertraline, and fluoxetine can cause tinnitus or temporary hearing changes in some people. It’s less common, but still real. If you start a new antidepressant and suddenly hear a constant high-pitched tone, don’t ignore it.

How Does the Damage Happen?

Your inner ear is a tiny, complex system. Sound waves travel through the cochlea, where thousands of hair cells vibrate and send signals to your brain. These cells are incredibly sensitive.

Ototoxic drugs attack them in a few ways:

- They create oxidative stress - basically, a chemical overload that burns out the cells.

- They block blood flow to the inner ear, starving the hair cells of oxygen.

- Some directly poison the cells by binding to their DNA or disrupting their energy production.

The damage usually starts at the top end of your hearing range - around 4,000 to 8,000 Hz. That’s where you hear birds chirping, children’s voices, or the 's' and 'th' sounds in speech. You might not notice it at first because you’re still hearing conversations fine. But over time, it spreads. By the time you’re struggling to follow talks in noisy rooms, the damage is already widespread.

Why Standard Hearing Tests Miss the Warning Signs

Here’s the scary part: most doctors don’t check for this. A routine hearing test at your GP’s office usually only goes up to 4,000 Hz. But ototoxic damage starts above that - at 6,000 Hz, 8,000 Hz, even 12,000 Hz.

One Reddit user shared how they lost hearing at 6,000 Hz after their third cisplatin cycle. Their oncologist didn’t know to test above 4,000 Hz. By the time they saw an audiologist, the loss was permanent.

That’s why baseline testing is non-negotiable. Before starting cisplatin, gentamicin, or any high-risk drug, you need a full high-frequency audiogram. It should test up to 12,000 Hz. Without it, you’re flying blind.

What Monitoring Actually Looks Like

Good ototoxicity monitoring isn’t just one test - it’s a plan.

For cisplatin patients:

- Baseline audiogram before the first dose - must include 8,000 Hz and 12,000 Hz.

- Repeat testing after each treatment cycle - ideally within 1-2 weeks.

- Use otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing - this detects hair cell stress before you even lose hearing on a standard test.

For aminoglycosides:

- Baseline test before starting.

- Testing after every 5-7 days of treatment.

- Focus on 8,000 Hz and 12,000 Hz - these frequencies show early damage.

Studies show that when patients get this kind of monitoring, the chance of severe hearing loss drops by 30-50%. That’s huge. It means you might keep your hearing if you’re watched closely.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Some people are more vulnerable than others.

- Children - their ears are still developing. Cisplatin can delay speech and language learning. One study found 35% of kids treated for cancer had undiagnosed hearing loss that affected their school performance.

- People with kidney problems - many ototoxic drugs are cleared by the kidneys. If your kidneys aren’t working well, the drugs build up in your system.

- Those with family history - certain genetic mutations, like m.1555A>G, make you 100 times more likely to lose hearing from aminoglycosides. It’s rare, but if your parent or sibling lost hearing after antibiotics, ask about genetic testing.

- People on multiple ototoxic drugs - combining cisplatin with aminoglycosides or even high-dose aspirin multiplies the risk.

What You Can Do - Even If You Can’t Stop the Drug

You might not be able to avoid a life-saving medication. But you can protect your hearing.

- Ask for a baseline hearing test before starting any high-risk drug. Don’t wait for your doctor to bring it up.

- Know the early signs - ringing in the ears (tinnitus), muffled sounds, trouble hearing in noisy places, dizziness. These aren’t just side effects - they’re red flags.

- Request high-frequency audiometry - make sure your audiologist tests up to 12,000 Hz. Most clinics can do this, but you have to ask.

- Track your symptoms - keep a simple journal: ‘Day 3: ringing started after IV dose.’ This helps your team spot patterns.

- Push for coordination - your oncologist or infectious disease doctor should be talking to your audiologist. If they’re not, ask why.

New Hope: What’s Changing

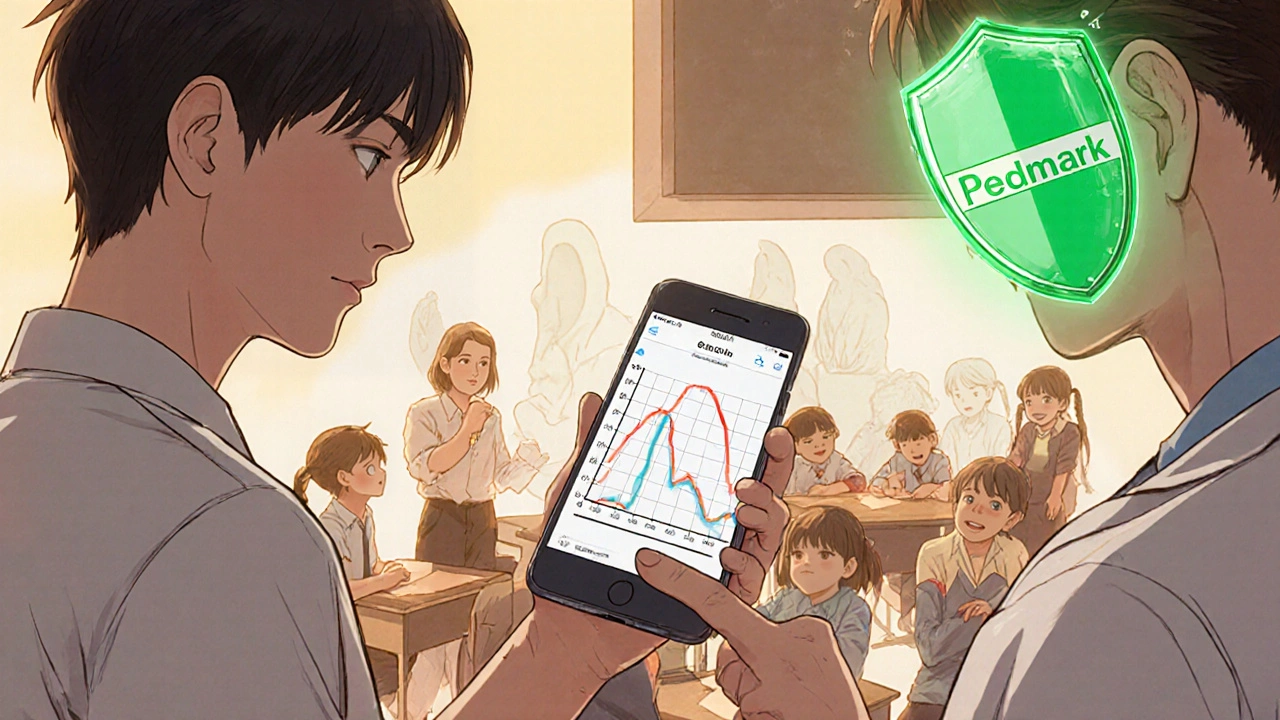

There’s progress. In 2022, the FDA approved a new drug called sodium thiosulfate (Pedmark) specifically to protect children’s hearing during cisplatin treatment. In trials, it cut hearing loss by 48%.

Researchers are also testing N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant, to shield ears from aminoglycoside damage. Early results look promising.

And new tech is making monitoring easier. Smartphone apps are being developed that can test your hearing at high frequencies at home. Imagine checking your hearing on your phone after each chemo session - no clinic visit needed.

But here’s the catch: adoption is still slow. Only 45% of U.S. cancer centers have formal ototoxicity monitoring programs. That means you might have to be your own advocate.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Healing your body shouldn’t cost you your hearing. But right now, it often does. Over 15 million people in the U.S. alone take ototoxic drugs each year. The economic cost? Over $1 billion annually - from hearing aids to lost work and speech therapy.

But beyond the numbers, there’s quality of life. One patient described tinnitus after gentamicin as ‘a constant scream in my head that made sleep impossible.’ Another said they stopped going to family dinners because they couldn’t hear anyone over the background noise.

These aren’t minor inconveniences. They’re life-changing.

If you or someone you love is on a drug like cisplatin or gentamicin, don’t assume your hearing is fine. Ask for a test. Demand high-frequency screening. Track the symptoms. Your ears can’t tell you when something’s wrong - you have to speak up.

Can ototoxic hearing loss be reversed?

No. Once the hair cells in your inner ear are destroyed, they don’t regenerate. That’s why early detection is so critical - you can’t restore lost hearing, but you can stop further damage by adjusting medication or adding protective treatments.

Are over-the-counter painkillers like ibuprofen ototoxic?

High doses of NSAIDs like ibuprofen or aspirin can cause temporary tinnitus or hearing changes, especially with long-term use. But this is usually reversible when you stop taking them. It’s not the same as permanent damage from cisplatin or gentamicin.

How often should I get my hearing tested if I’m on cisplatin?

You should have a baseline test before your first dose, then another after each treatment cycle - typically every 1-3 weeks depending on your schedule. Testing should include frequencies up to 8,000-12,000 Hz, not just the standard 4,000 Hz.

Can I switch to a less ototoxic drug like carboplatin instead of cisplatin?

Sometimes, yes. Carboplatin is much less likely to cause hearing loss, but it’s also less effective against certain cancers. Your oncologist will weigh the risk of hearing damage against the need for maximum cancer control. Ask if carboplatin is an option for your specific case.

Is genetic testing for ototoxicity worth it?

It’s most useful if you or a close family member had sudden hearing loss after taking antibiotics like gentamicin. A simple blood test can check for mutations like m.1555A>G, which make you extremely sensitive. Routine screening for everyone isn’t recommended yet - but if you have a family history, it’s worth discussing with your doctor.

What should I do if I notice ringing in my ears during treatment?

Don’t wait. Tell your oncologist or prescribing doctor immediately. Ask for a referral to an audiologist for high-frequency testing. Tinnitus is often the first warning sign. Catching it early can mean the difference between mild hearing loss and severe, permanent damage.

Author

Mike Clayton

As a pharmaceutical expert, I am passionate about researching and developing new medications to improve people's lives. With my extensive knowledge in the field, I enjoy writing articles and sharing insights on various diseases and their treatments. My goal is to educate the public on the importance of understanding the medications they take and how they can contribute to their overall well-being. I am constantly striving to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in pharmaceuticals and share that knowledge with others. Through my writing, I hope to bridge the gap between science and the general public, making complex topics more accessible and easy to understand.