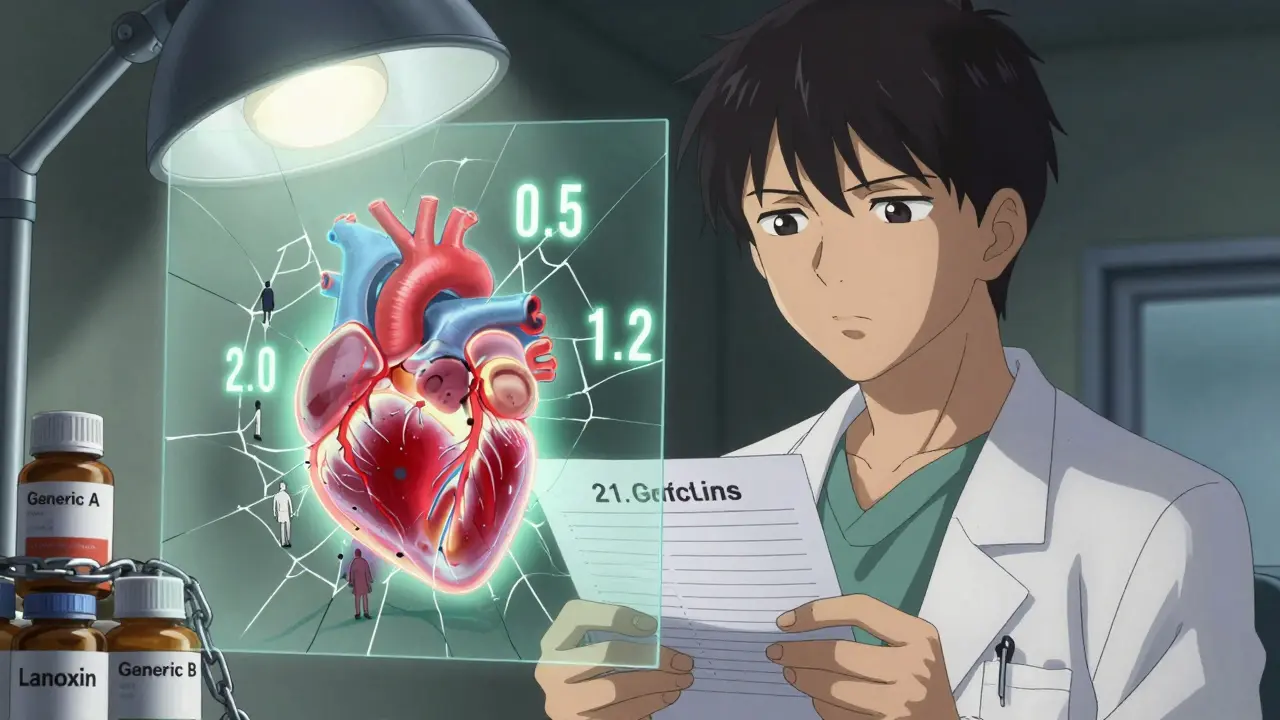

Switching from one digoxin generic to another might seem like a simple cost-saving move-but for patients, it can be risky. Digoxin isn’t like most medications. It’s a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug, meaning the difference between a safe dose and a toxic one is tiny. The target blood level? Just 0.5 to 2.0 ng/mL. Go a little too high, and you could get nausea, blurred vision, or dangerous heart rhythms. Go too low, and your heart failure or atrial fibrillation could get worse. That’s why the way your body absorbs digoxin matters more than you think.

Why Digoxin Is Different

Most drugs have a wide safety margin. If you take 10% more or less, your body handles it. Not digoxin. It’s absorbed inconsistently, especially between different generic brands. The FDA treats it like a new drug-not because it’s unsafe, but because small changes in absorption can cause big problems. That’s why, back in 2002, the FDA required all generic digoxin products to prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand-name version, Lanoxin. That means their AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration) must fall within 80-125% of Lanoxin’s.

On paper, most generics pass. Studies in Saudi Arabia and Estonia showed specific generics matched Lanoxin’s absorption in healthy volunteers. But here’s the catch: bioequivalence is based on averages. If one person absorbs only 45% of the drug, but the group average hits 90%, the FDA still approves it. That’s fine for most drugs. For digoxin? It’s a ticking time bomb.

The Real Problem: Switching Between Generics

The FDA approves each generic against Lanoxin-but not against other generics. That means Generic A might be bioequivalent to Lanoxin. Generic B might be too. But Generic A and Generic B? No one tested them against each other. And that’s where trouble starts.

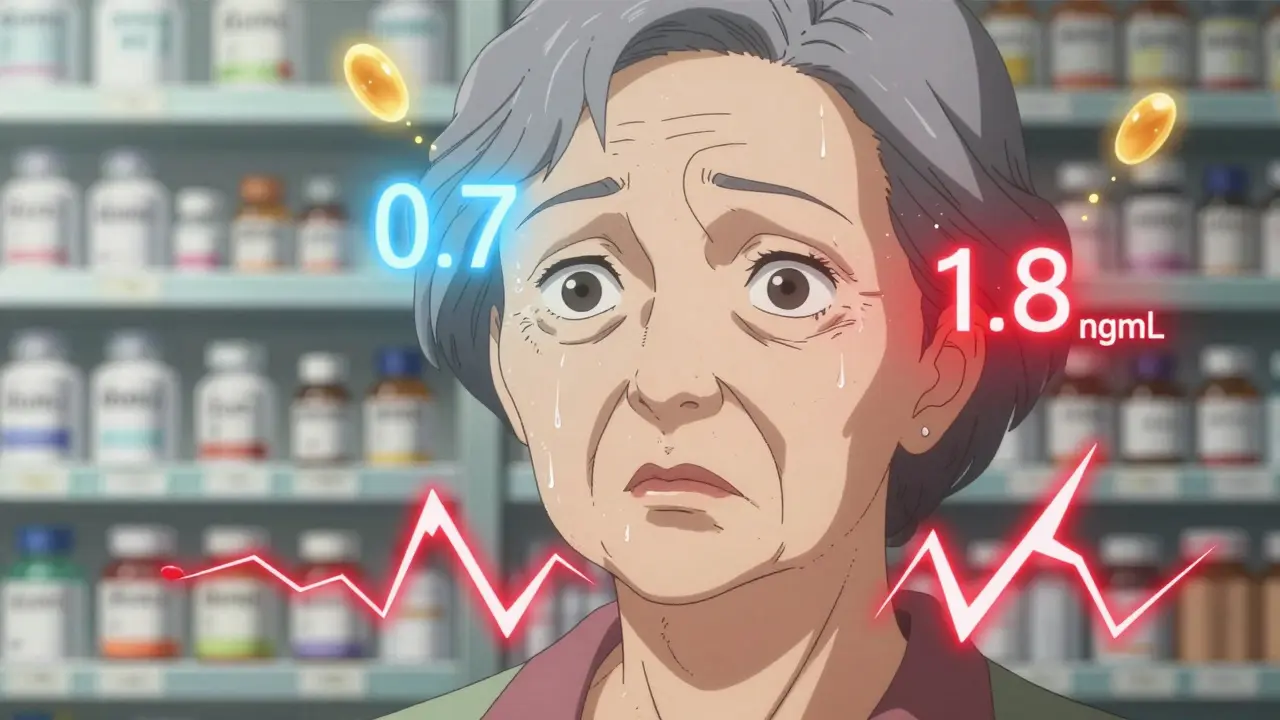

Imagine a 78-year-old woman on digoxin for atrial fibrillation. She’s been stable on Generic A for two years. Her doctor switches her to Generic B because her pharmacy changed suppliers. No warning. No lab test. Three days later, she feels dizzy. Her pulse is irregular. A blood test shows her digoxin level jumped from 0.7 ng/mL to 1.8 ng/mL-right at the top of the therapeutic range. She’s lucky. No hospitalization. But she could have gone into cardiac arrest.

Case reports show exactly this. Switching between generics has caused digoxin levels to shift by more than 25% in some patients. That’s not a typo. That’s a 25% change in a drug where the safe range is only 1.5 ng/mL wide. And elderly patients-who make up most digoxin users-are especially vulnerable. Their kidneys clear digoxin slower. Their bodies absorb it differently. And they’re often on five or six other meds that interact with it.

Formulation Matters Too

Not all digoxin forms are the same. Tablets? Absorption is around 60-80%. But the liquid form? It’s absorbed much better-70 to 85% of the intravenous dose. That’s why switching from a tablet to a liquid, even within the same brand, can change your blood levels. Pharmacists sometimes switch patients to liquid for easier dosing. But without checking digoxin levels afterward, it’s like driving blindfolded.

Even the tablet’s ingredients matter. Fillers, binders, coatings-all can affect how quickly the drug dissolves. One generic might release digoxin in 30 minutes. Another might take 90. That’s enough to push levels out of the safe zone, especially if you’re already on the edge.

What Doctors Should Do

There’s no excuse for guessing. If you start digoxin, get a blood test 4 to 7 days later. That’s the standard. But what about after a switch? You need another test. The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology both say: Check levels after any formulation change. That includes switching pharmacies, insurers, or generic manufacturers.

Don’t wait for symptoms. By the time someone feels nauseous or sees halos around lights, it’s already too late. Check the level 3 to 5 days after the switch. Draw the blood just before the next dose-that’s the trough level, and it’s the most accurate for monitoring. Target 0.5-0.9 ng/mL for heart failure patients. Studies show lower levels mean less death risk. For atrial fibrillation, 0.5-1.2 ng/mL is often enough.

What Patients Should Know

If you take digoxin, know your brand. Write it down. If your prescription comes in a different-looking pill, ask: “Is this the same one I was on?” Don’t assume. If the pharmacy says, “It’s just a different generic,” ask if they checked with your doctor. If they say no, push back.

Keep a log. Note any new symptoms: dizziness, upset stomach, irregular heartbeat, blurry vision. Bring it to your next appointment. Tell your pharmacist too. They’re your first line of defense.

And never, ever stop taking it without talking to your doctor. Digoxin’s half-life is 36 hours. It sticks around. Stopping suddenly can cause rebound heart problems.

Why This Isn’t Fixed

The FDA knows this is a problem. They list only three generic digoxin products with an “AB” rating-meaning they’re approved as bioequivalent. But there are dozens on the market. Why? Because the system allows it. The rules say: prove equivalence to the brand. Not to other generics. And manufacturers don’t test each other. Why spend money on a study that won’t get you more sales?

Meanwhile, patients get caught in the middle. Pharmacies switch based on price. Insurance plans change preferred brands. Doctors don’t always know what’s in the bottle. And patients? They’re told it’s “the same drug.” But with digoxin, it’s not.

What’s the Solution?

Two things: consistency and monitoring.

First, stick with one brand-generic or brand-name-once you’re stable. If your doctor prescribes Lanoxin, ask if you can keep it. If you’re on a generic, don’t switch unless absolutely necessary. If you must switch, demand a digoxin level test before and after.

Second, make sure your doctor checks your levels regularly. Not just once a year. Especially if your kidney function changes, you start a new med (like amiodarone or verapamil), or you get sick. Digoxin levels rise when your kidneys slow down. That’s common in older adults. One missed test can be all it takes.

There’s no magic fix. But if you treat digoxin like the high-risk drug it is, you can avoid disaster. It’s not about trusting generics. It’s about knowing that with NTI drugs, trust isn’t enough. Data is.

Bottom Line

Digoxin generics work. Many are bioequivalent to the brand. But they’re not all the same to your body. The risk isn’t in taking a generic-it’s in switching between them without checking your blood levels. If you take digoxin, treat it like insulin or warfarin: consistent, monitored, and never taken lightly. Your heart will thank you.

Author

Mike Clayton

As a pharmaceutical expert, I am passionate about researching and developing new medications to improve people's lives. With my extensive knowledge in the field, I enjoy writing articles and sharing insights on various diseases and their treatments. My goal is to educate the public on the importance of understanding the medications they take and how they can contribute to their overall well-being. I am constantly striving to stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in pharmaceuticals and share that knowledge with others. Through my writing, I hope to bridge the gap between science and the general public, making complex topics more accessible and easy to understand.